There are stories from the motorsport’s past that appear to be exactly between a movie screenplay and pure mythology, specially if you compare them with what motorsport is today.

Tazio Nuvolari finishing 13th at 1946 Coppa Brezzi holding the steering wheel in his right hand whilst coughing up and spitting blood or managing to almost win the 1948 Mille Miglia — with 27 minutes off the car behind him — without the bonnet, a damaged leaf spring and the mechanic sitting next to him with no seat, always seemed the work of a good author with a lot of imagination. But, apparently, it’s all true.

The story of how Duncan Hamilton and Tony Rolt won the 1953 24 Hours of Le Mans is another very entertaining tale that would be impossible to replicate nowadays. And it certainly happened.

Born in Cork, Ireland, Hamilton was brought up in relative obscurity. Prior to his 20th birthday, Europe was already embroiled in the Second World War. As a result, he spent the war years as part of the Fleet Air Arm flying Lysanders. After the war ended, he opened a car garage. During the years between the war ending and the start of the 1950s, Duncan started racing in local events. He cut his teeth in such pre-wars as the MG R-type and the Bugatti Type 35B. After racing a Maserati 6CM in 1948, Duncan graduated to a Talbot-Lago Grand Prix car.

He participated in five World Championship Grands Prix — with no results — and eighteen non-Championship Formula 1 races. His best results in the non-Championship events were a 4th place in the 1948 Zandvoort Grand Prix with a Maserati 6CM, 3rd in the 1951 Richmond Trophy on a ERA B-Type, 2nd in the 1951 BRDC International Trophy on Talbot-Lago T26C, 3rd in the 1952 Richmond Trophy still on a T26C, and 4th in the 1952 Internationales ADAC Eifelrennen.

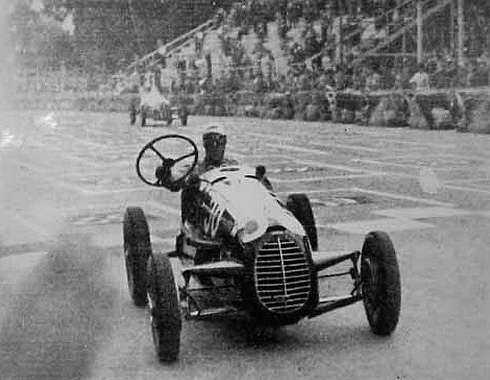

Under the rain, Hamilton had few peers. In his Talbot-Lago, he eclipsed even Juan Manuel Fangio at the soaking BRDC International Trophy race at Silverstone in 1951, when he finished second to Reg Parnell, but a long way ahead of Fangio who went on to win the Championship that season.

At the 1953 24 Hours of Le Mans Ferrari cars were the cars to beat, but Jaguar — with their revolutionary brake discs-fitted C-Type — had been focusing its attention on La Sarthe’s race. It’s 100% true that the Jaguar in which Hamilton and Rolt were to compete got disqualified before the race start, because the British team accidentally took a car bearing the same race number as another competitor on track for the practice session.

Hamilton and Rolt accepted the disqualification and simply decided to go to the local pub, while Jaguar’s team manager Lofty England was fighting with the Le Mans race commission in order to get the Hamilton/Rolt Jaguar back on the grid.

England didn’t fail, and the Jag was in.

At 10 am on race day both drivers were so drunk that nobody would have let them sitting behind the steering wheel of any car; the show had to go on tho, and Jaguar needed them. The endurance started.

Hamilton was then strapped in to take the start of the hardest track race in the world. In an attempt to sober him up, the team supplied coffee at every pit-stop; this — according to Hamilton — made his arms twitch uncontrollably and the only thing to solve the problem was more alcohol — Brandy in fact — in order to fend off the looming hangover. The Brandy may have controlled the arm twitching and defended Hamilton from a world of room-spin and vomiting, but it must have also helped when a bird hit his face at 210 km/h, breaking his nose.

Both Lofty England and Tony Rolt have since denied that both drivers were drunk.

Of course I would never have let them race under the influence. I had enough trouble when they were sober!

Lofty England

A week after the 1953 Le Mans win, Hamilton drove to Oporto to prepare for the Portuguese Grand Prix. Held on the Circuito da Boavista, he was leading into the first corner of the race when he crashed his Jaguar heavily into an electricity pylon and the accident cut off the power supply to the city for several hours.

His Jaguar cartwheeled, throwing him out of the car and into a tree. He hung there for about a minute, before falling down on the side of the circuit. Barely conscious, he moved his legs just as a Ferrari raced by, nearly taking Hamilton’s left boot with it. He was taken to hospital for an emergency operation, though the medical facilities did not extend to anaesthetic.

“Why is it dark in here?” Hamilton mumbled.

“Because the pylon you crashed into fed this hospital’s electricity”, replied the surgeon.

“Why aren’t I anaesthetised?”

“Because the anaesthetist went to watch the motor race you were in!”

Hamilton passed away in 1994 and he is regarded as the epitome of the old school English competitor such as his contemporaries Mike Hawthorn and Peter Collins.

Words by Touch Wood, The Autobiography of the 1953 Le Mans Winner.